Vietnam’s legacy in Minooka

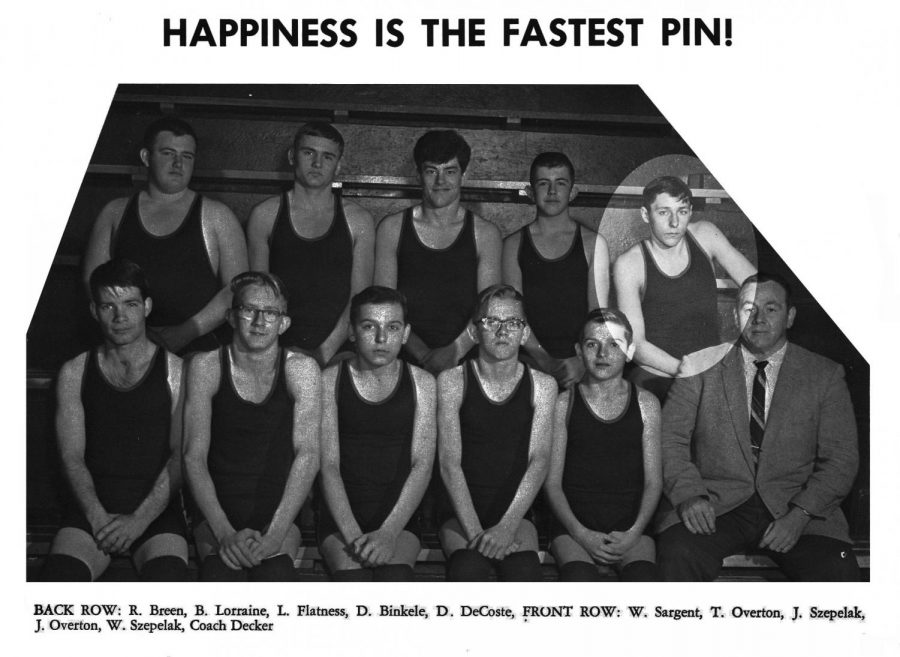

The 1965-66 wrestling team include David Anthony DeCoste, located in the back right. He died in the war, and later a wrestling award at Minooka was named for him.

This was originally printed as two stories in the Sept. 20 and Oct. 23 issues of the Peace Pipe Chatter.

Vietnam. The Cold War. Civil Rights. Feminism. LBJ doesn’t run again. Nixon is elected. Arm bands. Torched draft cards. Space Race. Olympics in Mexico City. Sex, drugs, and rock and roll.

It’s been 50 years since that influential year in America’s history.

Fifty years since the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

The assassination of Robert F. Kennedy.

The Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Fifty years since the flame of civil disobedience, the fervor of anti-war sentiment, and the fight for policy change set the precedent for half a century more of unwavering zeal.

We often regard these events in terms of their influence on a national and international scale, and their impact on the small towns and small people are often lost within the shadow of the “Big Picture” we read in our history textbooks.

Day-to-day life in rural communities like Minooka in ’68 exist as a minor detail in the vast and complex story of our nation; it’s easy to forget that these ground breaking incidents touch the lives of everyone—even people in those farm-based and isolated communities lost in the broad cornfields of the Midwest.

We see countless portraits of cities in the ’60s and ’70s, but seldom do we pay any mind to the suburbs in this era post-conformity.

The protests and riots and political showdowns may not have taken place in these rural communities, but they certainly left their mark—and Minooka was no exception.

Minooka in ’68

The MCHS student body grew from a meager 400 to approximately 3,000 over the course of just 50 years. We went from a small agriculture-based community where everyone’s family had ties to a farm to our present population where there’s only a handful of students with a connection to Minooka’s former shining glory.

Sure, our school is flanked with cornfields and we still hold FFA meetings, but the farming-based education and agrarian lifestyle has since been replaced with college courses and a bustling suburban tone.

In ’68, Central and South campuses didn’t exist; students took classes at what is now the Primary Center on Church Street in downtown Minooka. A popular club of choice that we don’t see in Minooka today was the Future Homemakers of America.

Furthermore, there wasn’t a football team until 1971, and the only girls varsity sport at MCHS was cheerleading.

Until 1973, when the first girls volleyball team began, girls could participate solely in intramural sports through the Girls Athletic Club.

Neither the Peace Pipe Chatter (only issue on file is Oct. 4, 1968) nor the yearbook mentioned any of the textbook-turning points in American history.

There wasn’t a single hint toward the Vietnam War in anything but the unspoken, unacknowledged aura of solemnity that undoubtedly loomed above the heads of those with fathers, brothers, and friends who might soon be drafted and sent overseas.

In many ways, Minooka existed as a microcosm for towns all across the United States from the strict dress code and the idolization of the American Dream to questioning conformity and challenging the status quo.

Minooka was never in the thick of the civil rights movement or the antiwar protests, but it was, and is, close enough to Chicago to have a personal attachment to the revolutionary advocacy and challenges to social norms that bloomed throughout the Vietnam War.

War Through a Domestic Lens

“I really came of age during the Vietnam War,” said Ms. Carolyn Kinsella, librarian.

Kinsella was attending junior high in 1968, and she was a freshman at MCHS in the fall of ’69.

She distinctly remembers coming home from school, plopping down on the couch in front of the TV with a snack in her lap watching The Bullwinkle Show when suddenly it would shut off and in its place would appear the image of a foreign jungle with a body count in bold, black lettering on the screen.

How many U.S. soldiers died?

How many Vietnamese?

That was it.

“Us and them,” she said.

Kinsella’s two older sisters were attending University of Illinois at this time. Older sisters whose friends were being drafted. In just a few years, she too would be watching the lottery with her friends, holding her breath.

“It was like bingo ping-pong balls,” said Kinsella. “Each one was like an egg with a day of the year on it, and if your boyfriend had one of those first numbers, well, you were sobbing.”

Kinsella knew a few of these young men who were drafted. Some of which never came home. Her boyfriend’s brothers, now her brother-in-laws, enlisted in the National Guard to avoid being drafted. Instead, they were called out to the riots. For instance, it was the National Guard, not the local police, who countered the outbreaks at Kent State in 1970 where students were protesting against the U.S. bombing of Cambodia.

“These young men were six-week wonders. They barely had any training, but they were the ones called out for the riots,” said Kinsella. “They weren’t really fighting an enemy; they were fighting their friends.”

Growing Skepticism

Since its birth, Minooka had been an isolated village. It was small, rural, and displaced.

In 1968, its inhabitants were the children of the Great Depression. They had lived through two world wars. They had fought, and they had won. Because of their all-knowing, righteous government leadership, they had beat the Nazis, they had beat the Japanese, and they were expecting to beat the Commies in Vietnam. The American government in all its glory and grandeur had lifted the nation from darkness and thrust it into light time and time again. Consequently, it was considered outrageous for young people to question the interests of the U.S. government.

If Capitol Hill and the Oval Office were sending troops abroad, people in Minooka, just like people all over the country, would support their wishes 100 percent until they saw it through.

“We couldn’t wear a black armband in protest,” said Kinsella in reference to when she attended MCHS. “We were pretty isolated and suppressive here. There weren’t protests in Minooka and Channahon. But we were close enough to Chicago to know people who were protesting.”

Democratic National Convention and its Legacy

The police assault on the Vietnam War protesters in front of the Chicago Hilton that fateful evening on August 28 was the cherry on top of American skepticism toward national politicians in this time.

In Minooka and across the nation, it was a culture shock.

Kinsella was watching her TV and eating her afternoon snack when Bullwinkle was interrupted again—this time with students, kids the age of her older sister, facing the brute force of the Chicago PD.

A young Kinsella asked her mother, “Why are the policemen beating those people?” to which her mother could only reply, wide-eyed and staring at the image on the screen: “I don’t know.”

Richard M. Daley, mayor of Chicago in ’68, wholeheartedly felt he was doing the right thing by turning the police force on the protestors.

He firmly believed he was preserving the integrity of his city. That the enemy was the anarchists in the streets. The communists. The children who had no idea what they were saying. He acted in what he called an effort to maintain peace. Kinsella, alongside hundreds of thousands of other Americans, suddenly began to question the morality behind Mayor Daley’s ideals.

“Not that my sisters and I were advocates,” said Kinsella. “We were goody little two shoes. We grew up here (in Minooka). We held very strong, religious, and moral beliefs of God and country. But even people like us started to question (the war) after we watched body counts and protesters being hit with billy clubs.”

The people in the streets would look directly into the cameras chanting over and over again: “The Whole World is Watching. The Whole World is Watching.”

Never pausing.

Never wavering.

Just a steady rhythm: “The Whole World is Watching.”

And for the first time ever, the whole world was watching. That didn’t happen in World War II when live television did not exist. The people only knew what the government told them. If the government officials in high offices knew about the Holocaust, they didn’t tell.

But in the Vietnam era, the world did know. It was staring them in the face.

It was so prevalent in the news that even isolated places in Minooka couldn’t turn a blind eye to history in the making as it was broadcasted in front of their very eyes without any political filters.

“We watched,” said Kinsella. “And because we watched, we changed.”

The War

“Vietnam. What a terrible situation,” said Mr. Kenneth Maas, South Campus hall monitor and former MCHS math teacher.

Maas was drafted in ’71 after a year of teaching at this school. The U.S. government’s Selective Service System statistics cite a total of 1,857,304 American draftees throughout the Vietnam conflict from August 1964 to February 1973, and Maas was just one of those young men whose lives at home would be put on pause on behalf of the war effort.

In 1970, fresh out of Northern Illinois University, Maas applied to several high schools for a math teaching position, but with a draft number of 185 out of 190, his interviews were usually cut short.

“When I was interviewed for these jobs, they would ask me what my major was, and they would ask me what my lottery number was. When I told them, they knew I was going to get drafted so the interview ended pretty quickly,” said Maas. “This got to be frustrating for me because I knew that this was going to be the way it was.”

Few young graduates seeking a teaching position were looking for a job in a town as small as Minooka, and Maas was the only individual signed up for an interview for MCHS. Growing up on a farm, such an environment would undoubtedly be familiar to him.

Fortunately for Maas, the principal of Minooka at the time, Al Mattingly, was a veteran. He asked Maas the same questions as the other employers; but this time, after he asked Maas about his draft number, the interview miraculously kept going. Shortly thereafter, Maas was hired and began his first year teaching at Minooka. In January of 1971, he received his draft notice. Mattingly wrote a letter to the draft board in Maas’s favor, convincing them to postpone his draft until the end of that school year in June. Maas then took a military leave of absence and worked as a stateside mathematical assistant throughout part of the war. He worked in the controller’s office. His job was to look at “top secret” information, make a report, and send it to someone who would then decide how much money was needed where it was filtered on behalf of the war effort. This “top secret” label meant he had to be careful about what he said, to whom he said it, and what he did.

“I just said I did some math problems, and that was it,” said Maas. “In all honesty, I had a great job. I was very fortunate. My experience in the army was a lot better than it could’ve been.”

The Vietnam War, like with many families at the time, was a huge part of Maas’s life. His older brother was drafted in ’65, and his younger brother was drafted in ’70, the same year Maas would’ve been drafted if he hadn’t been attending college.

“He doesn’t like to talk about it,” said Maas, referencing his older brother who was sent to Vietnam in the thick of the conflict. “I know he saw some things there that were not very positive. When he first came back, he was not easy to live with. He flew off the handle at a moment’s notice, and that happened for a while. Most of the people who are Vietnam veterans usually don’t say good things about their experiences over there.”

As a result of the conflict, 52,220 young American men died or went missing according to the National Archives, 30.4 percent of which were draftees. Two former Minooka students, Charles Warner Becker (read story of Becker here) and David Anthony DeCoste (read story of DeCoste here), were killed in Vietnam. At one point, there were over 500,000 soldiers on foreign soil fighting what Maas referred to as little more than “a waste of time, a waste of human resources, and a waste of a lot of money.”

“We lost all those soldiers for what was more of a political war than a military war,” said Maas. “I know from talking to my older brother that the mission was to capture a hill or a section, and they would. They’d lose some soldiers, and a few months later they got away from that and the (Vietnamese) army took it back over. Why we got it and why we gave it back, I have no idea. Body count seemed to be the most important thing. We lost 20 soldiers, but they lost 50 soldiers. That must mean we were winning the war. Just a lot of propaganda to try and get the public to agree to what we were doing.”

“War’s not good,” said Maas. “Someone said ‘War is hell,’ and it is.”

Coming Home

Maas was eager to return home after the conflict. He looked forward to teaching again, though he was slightly nervous because he had been “out of the loop” for so long. Nevertheless, Mattingly, now the superintendent of Minooka, welcomed him with great enthusiasm, giving him tenure after his first year back and ensuring he had support throughout his readjustment.

“I think I did okay,” said Maas. “It was good to see the kids, and the conversation about my service didn’t last very long.”

Maas stressed how the military throughout the ’60s and ’70s was not as respected as it is now.

“When you wore the uniform and you were not on the military base, people kind of stayed away from you,” said Maas. “Vietnam had a very negative image in this country. On the newscasts, they showed the (My Lai) massacre where the U.S. shot up a (Vietnamese) village and killed innocent people. That stuck.”

Back at school, some of the students and faculty members shied away from him.

“When (people from the military) came home, they put the uniform away and put on civilian clothes,” said Maas. “Now, they wear their uniforms in public, and they’re respected for what they (do).”

While the American population at that time had limited tolerance for individuals in the military, career soldiers treated draftees with similar disrespect.

“I had to make sure that I was the loving, caring individual that you’re supposed to be,” said Maas. “When you’re a draftee, career soldiers don’t really have much patience for you. You just kind of bite your tongue, and I had to make sure I didn’t carry my negative attitude toward the army over back home. And I don’t think I did.”

Why Does it Matter?

Minooka was and is a small town often passed off as a mere suburb of Chicago, but it represents a trend that manifested itself across high schools and communities in every part of the United States.

MCHS wasn’t immune to the political influence of the Vietnam era. Its students didn’t shun the music that protested the war that their government stood so proudly behind.

Following the victory of students from a public school in Des Moines, Iowa, to wear black armbands in protest of the Vietnam conflict, a few Minooka students in the class of ’73 used the same arguments to fight against the dress code.

At that time, Minooka girls were expected to wear skirts almost touching the floor, and boys had to tuck in their shirts with a polished belt. Once the Iowa students were suspended and the issue worked its way up to the 1969 Supreme Court case of Tinker v. Des Moines, the justices ruled 7-2 in favor of the students. The court said, “Students don’t shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate.”

This laid the foundation for a similar endeavor in MCHS just four short years later. Kinsella was among the graduating class that involved the ACLU in pushing for the elimination of the Minooka’s strict dress code and embraced the era of long hair and miniskirts with open arms.

The Vietnam conflict left a lasting effect on MCHS. One teacher served, and two students died. Families in the community felt the weight, loss, and heartache of the Vietnam War firsthand.

Though Minooka is increasing exponentially in size since 50 years ago, though girls can wear jeans to school and boys can sport a ponytail, it still exhibits the innumerable ways an isolated community cannot escape the grasp of history when it’s in the making.

Jillianne Overman • Nov 25, 2021 at 12:33 am

Mr Maas was my math teacher when I attended MCHS. I graduated in 2000. I loved his sarcastic and dry sense of humor. I’ll never forget his facial expressions and short humorous responses to my questions, we had a lot of fun in every class. He was shocked when I aced his midterm exam and he gave me the math award that year. These are some of the best memories I take away from my time at MCHS. Mr Maas and teachers like him made our small town high school pretty great!

Cheryl Smania Nelson • Oct 26, 2018 at 9:04 am

I was born and raised in Minooka and was a classmate of Carolyn’s, graduating in 1973. Because the school and community were so small, we were a family. I loved my town back then. I do miss the small town atmosphere. This article was very well written and accurate. I enjoyed the read. It brought back many memories. Congrats on an interesting piece.

Michael E Hadaway • Oct 26, 2018 at 8:54 am

That was an AWESOME article!!